Summary

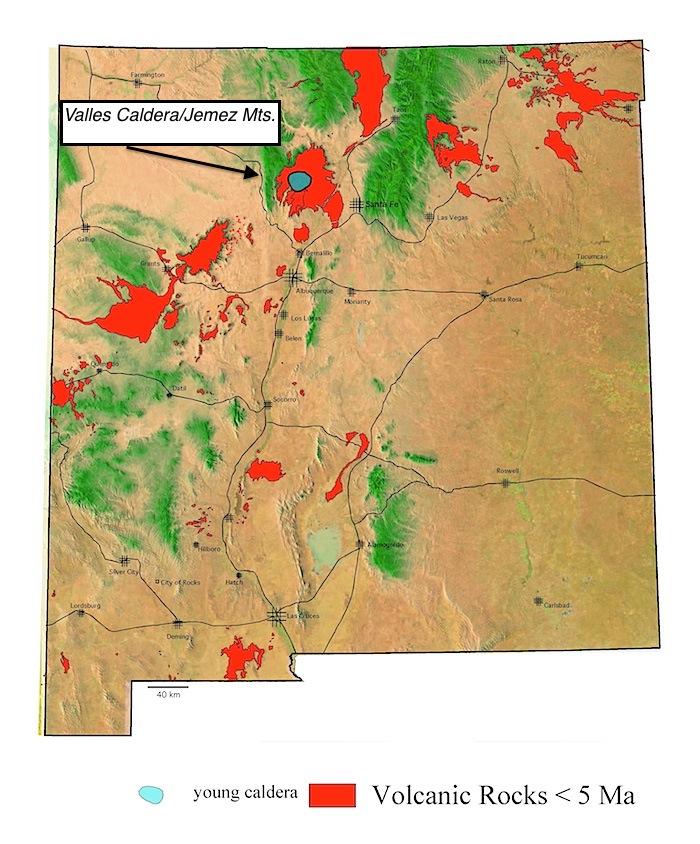

When you drive or hike through the Jemez Mountains, you are looking at a landscape created by young volcanic eruptions. The Jemez Mountains are volcanic mountains; eruptions have continued intermittently from 14 million years ago to as recently as 40,000 years ago. The Valles Caldera is a supervolcano eruption, like Yellowstone, and one of the largest young calderas on Earth. It formed about 1 million years ago when multiple explosive eruptions occurred that produced an immense outpouring of ash, pumice, and pyroclastic flows. It is considered by geologists to be still active.

Geologic Overview

Volcanic Field

Volcanic fields differ from the more popular conception of volcanoes, like Hawaii or the large volcanoes of the Cascades. Instead of one big volcano, volcanic fields consist of clusters of many small volcanoes. Overall, they are all characterized by many small centers of eruption (one to a few kilometers across) of fundamentally basaltic, but ranging to more silica-rich, compositions. The Jemez Volcanic Field, however, is different in that it began 14 million years ago as a normal volcanic field with the eruption of many small volcanoes and then experienced at least two extremely explosive caldera eruption events. The most recent of which, approximately 1.2 million years ago, formed the Valles Caldera and resulted in the eruption of the Bandelier Tuff, a thick ash flow unit that covers almost all of the earlier volcanic rocks from the field.

Valles Caldera

A caldera eruption differs from other volcanic eruptions. This is not the type of eruption where the summit peak is blown off and a crater is formed in the top of a large volcano.

Frequently asked questions:

What is a caldera?

A caldera forms when the ground collapses into the magma chamber as the magma is erupted in a series of explosive eruptions.

Yellowstone and the Valles Caldera are similar and two of the best examples of young calderas in the world.

How old is the Valles Caldera?

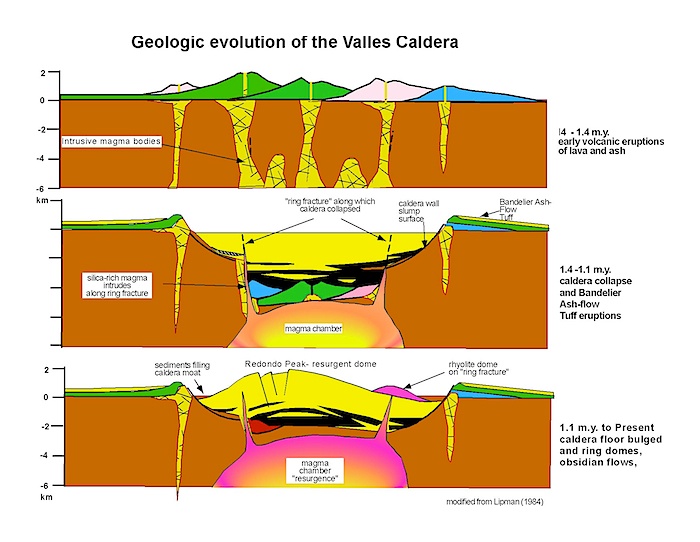

The caldera formed by collapse in a series of eruptions from about 1.4 to 1.1 million years ago. But the geologic evolution of the caldera has continued to today.

What type of volcanic rock has been erupted in the Jemez Mountains?

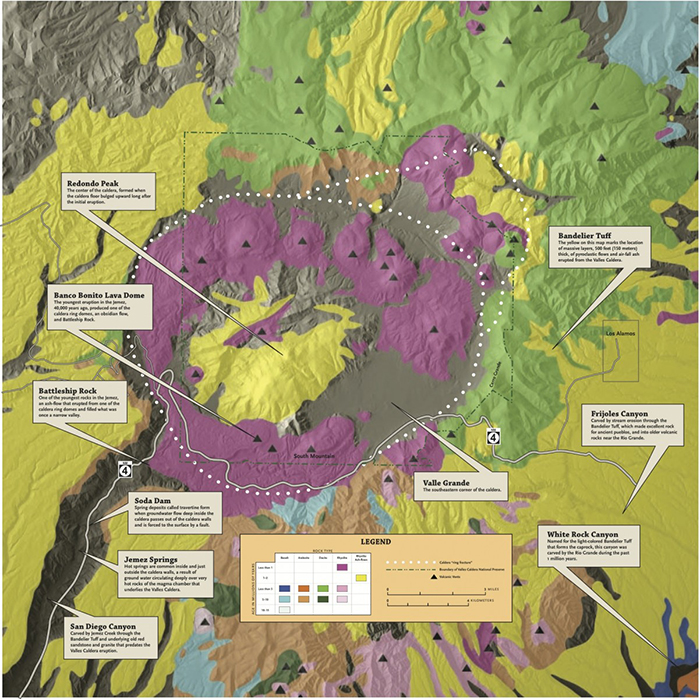

Early eruptions consisted of basalt lava flows, ash, pumice and ash-flows. As the Valles Caldera formed, air-fall ash and pumice must have covered most of New Mexico, and neighboring states, and has been identified as far east as Kansas. Pyroclastic flows moving away from the caldera formed what is today known as the Pajarito Plateau, and the sites of Los Alamos and White Rock. After the caldera formed, later eruptions formed domes and flows of rhyolite and obsidian that occur in a ring within the caldera.

What is an ash-flow or a pyroclastic-flow?

Hot, rolling clouds of incandescent ash and rock fragments that flow along the ground. The word pyroclastic comes from the Greek for “fire-rock”. Pyroclastic flows move very rapidly and are so hot that they weld into solid rock as they slow.

How high were the Jemez prior to the eruption?

Probably not much higher than they are today. This is not the type of eruption where a summit peak is blown off.

Is this a “supervolcano”?

Yes. The term “supervolcano” has recently been used to describe a caldera eruption, but it is a little misleading; calderas occur when multiple volcanoes interact and erupt in a series of eruptions, not from a single volcano or in a single very large eruption. It should be noted that volcanologists currently use the term "super eruption" to describe an eruption of several hundred cubic kilometers. But there is no definition for a "supervolcano." Presumably the non-volcanologist can be excused for the time being at least if they wish to refer to a volcano that hosted a super eruption as a "supervolcano."

Why is the Valles Caldera located here?

The Jemez Mountains are located along the western margin faults of the Rio Grande rift and are associated with the volcanic activity of this youthful and still active continental rift. The entire mountain range was built by a long record of many volcanic eruptions. The Valles Caldera was formed when multiple and long-lasting magma bodies merged into a large magma chamber.

Will the Valles Caldera erupt again?

This type of volcanism has a slow tempo. Even though the caldera appears inactive because it is grown over with trees, it probably looked like that for most of its history. The presence of hot springs shows that the caldera is part of a large, long-lived, and still active system.

General Summary: The Jemez Mountains and the Valles Caldera

- rifting in Jemez Mountains region began 16.5 Ma

- 13 to 10 Ma eruptions of basalt and rhyolite along Canada de Cochiti fault zone

- interbedded with basin-fill conglomerate and laharic breccias of Cochiti Formation

- between 10 and 7 Ma basalt and rhyolite erupted 1/2 the volume of the volcanic field

- 7 to 6 Ma eruptions of mixed magmas and sharp reduction in volcanic activity

- renewed basaltic activity at 4 Ma around margins and to east (Cerros del Rio volcanic field)

- Valles Caldera formed during eruption of Tshirege member at 1.12 Ma

- Bandelier Ash-flow Tuff erupted 1.2 Ma

- rhyolite composition

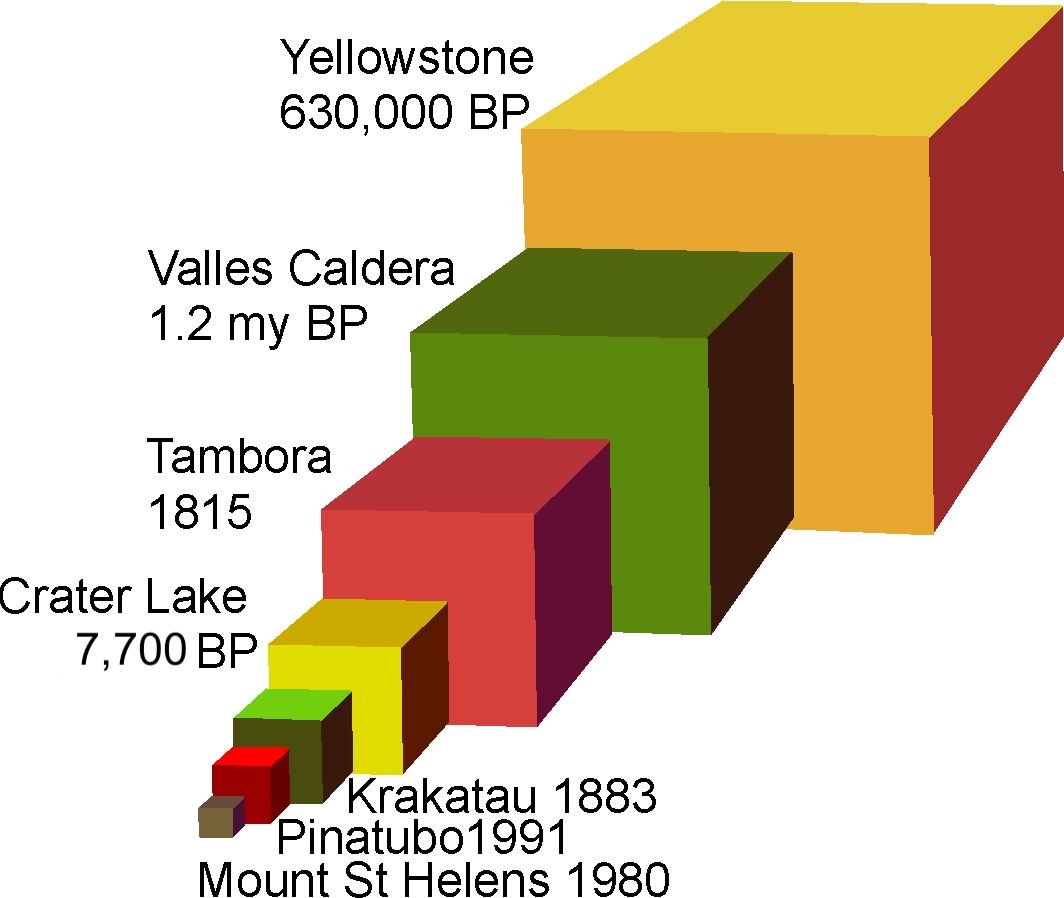

- 70 mi3 of Tshirege member (Note: Mt. St. Helens was 0.5 mi3)

- two distinct ash flow events make up the Bandelier: Tshirege Member and Otowi Member

- caldera collapse resulting from eruption from upper part of magma chamber

- roof of magma chamber at 5 to 6 km depth

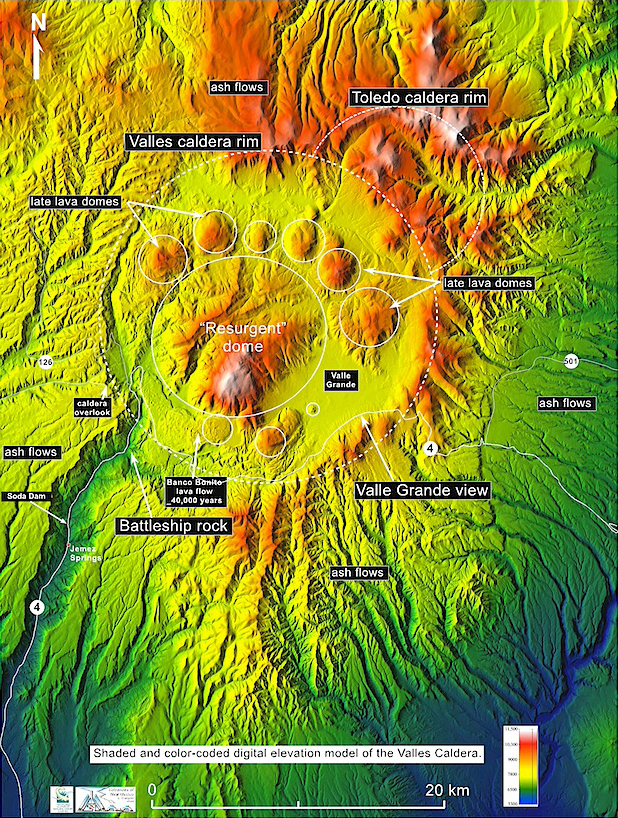

- resurgent doming of the caldera floor occurred during 100,000 yrs period after Valles collapse - due to buoyant rise of the magma chamber after unloading of upper part onto surface

- caldera fill deposits now exposed on summit of Redondo Peak, 1000 m above caldera moat

- after collapse volcanic activity continued with eruption of rhyolite domes

- domes erupted along caldera ring fracture until about 0.04 Ma

- youngest eruption is the 30 to 70 m thick Banco Bonito obsidian flow on SW ring fracture

- Battleship Rock ignimbrite resulted from explosive precursor to Banco Bonito eruption

Simplified geologic map of the Valles Caldera. The yellows are ash flow tuffs. The prink areas are late rhyolite lavas.

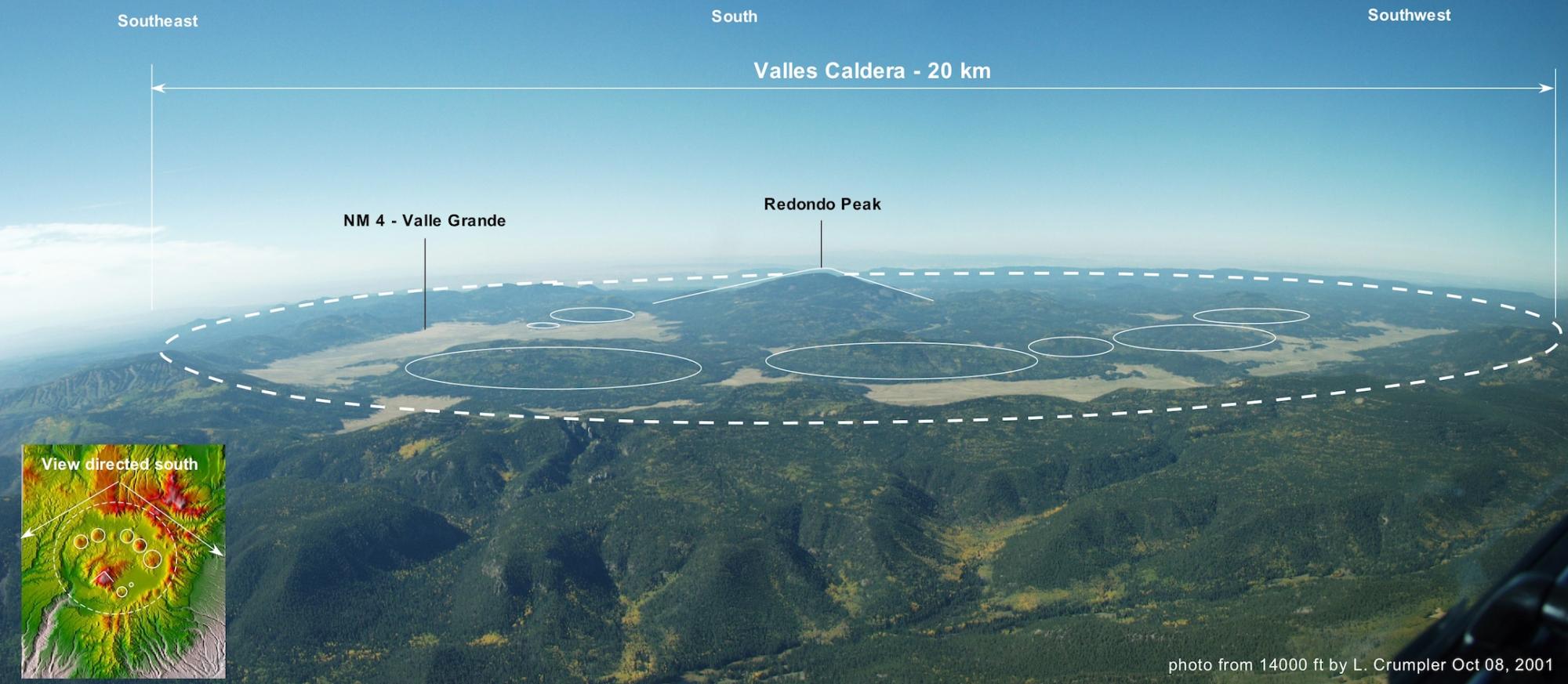

View across the floor of the Valles Caldera from New Mexico Highway 4. Ths view encompasses a small fraction of the caldera floor since the far wall is almost obscured by the central resurgent dome of Redondo Peak. Photo, L. Crumpler

This is a comparison of the volume of the Valles Caldera eruption and the volumes of the eruptions associated with some other famous calderas and supereruptions. Famous historic eruptions like Krakatau, Pinatubo, and Mount St Helens are trivial by comparison with eruptions that form calderas like the Valles Caldera.

The Valles Caldera. At more than 20 km across the Valles Caldera is so large that you really need to be high above the surface to actually see the whole structure in one perspective view. This view, looking south, was taken from a small plane at an altitude of 14,000 feet above sea level. Photo, L. Crumpler

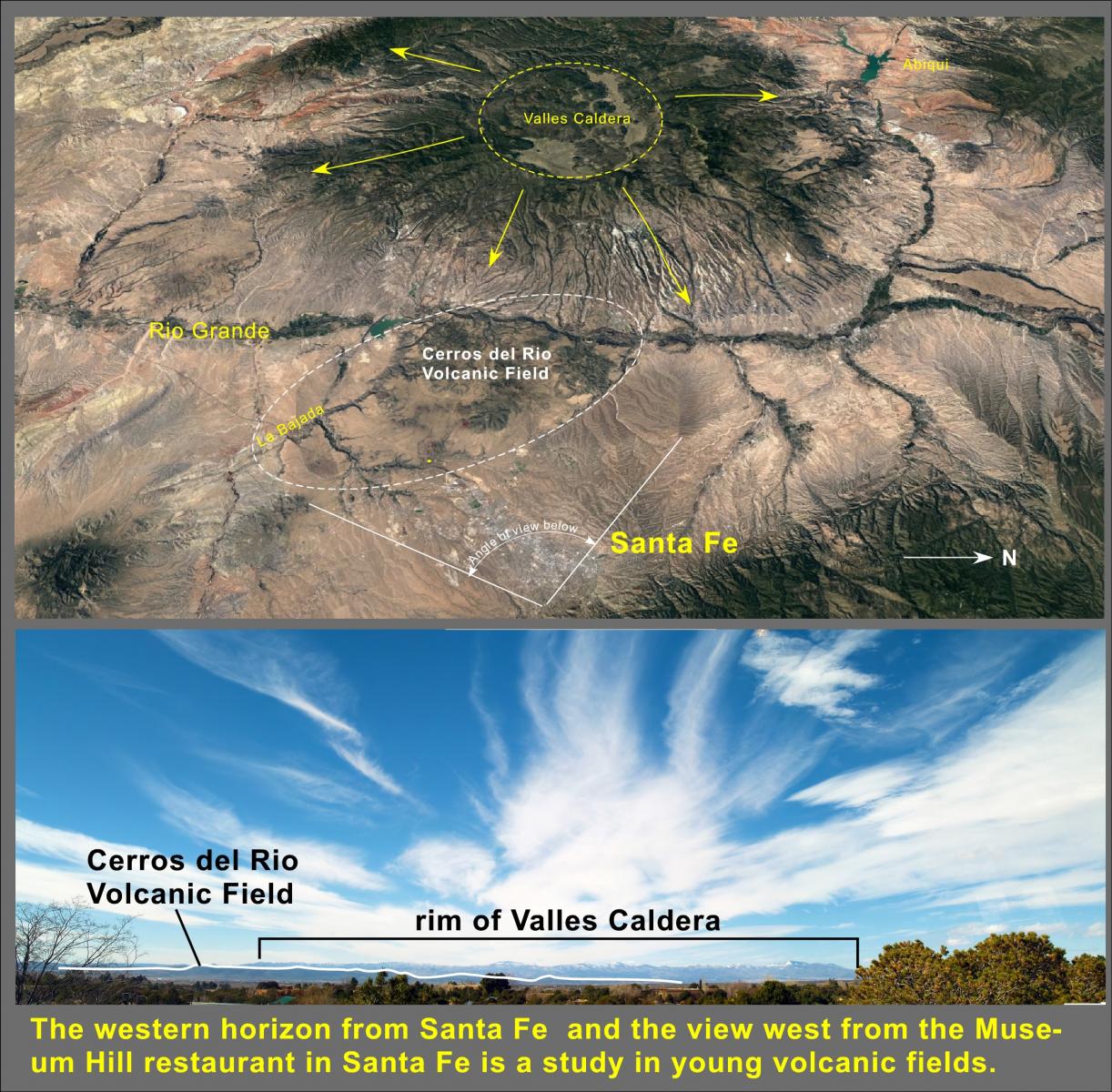

View west from Museum Hill, Santa Fe. Ironically, few Santa Feans realize that they live right next door to and can see from their windows the site of one of North America's latest super eruptions, the Valles Caldera. Photo L. Crumpler

The Valles Caldera "brooding" over the Albuquerque northern horizon.The Valles Caldera is so large that the profile of the caldera rim looks like an ordinary range of mountains on the horizon north of Albuquerque. The snowy peak in this view over the Rio Grande down 3rd Street and downtown Albuquerque s Cerro Redondo, the central uplift of the caldera floor. It is slightly offset to the southwest from the caldera center, hence it appears uncentered on the rim profile from this angle. This view looks north along 4th Street across the Rio Grande, National Hispanic Cultural Center, and down-town Albuquerque.

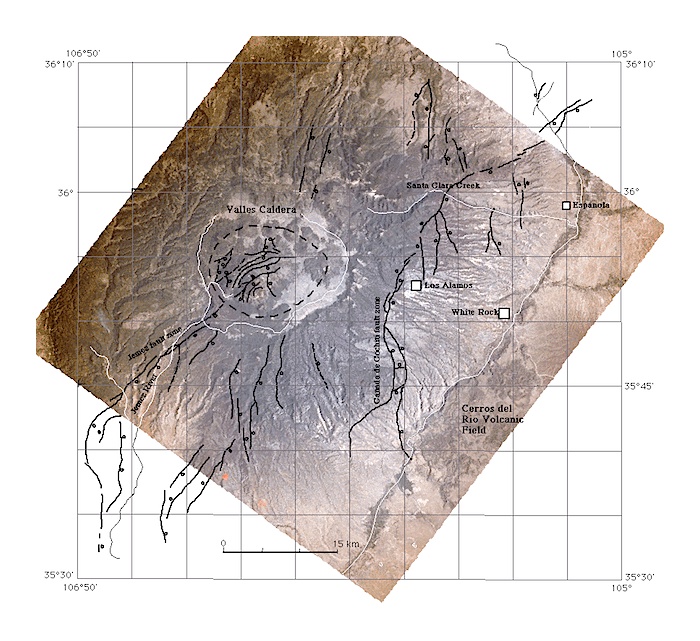

Because the Valles Caldera sits astride the western boundary faults of the Rio Grande rift, there are distinct through-trending faults.

The caldera is a result of collapse following the eruption of rhyolitic magmas from a large magma chamber. There was no large volcano prior to the collapse, just many volcanoes all clustered in the region. This is what makes giant calderas somewhat different than the type of volcanoes that most non-volcanologist have in mind when they think of a volcano. They are broad areas of intense volcanism rather than a single giant "volcanic mountain."

The floor of the caldera was occupied by a lake shortly after the collapse event. But it was short-lived because the floor of the caldera bulged upwards over the next several tens of thousands to 100,000 years resulting in the large mountain in the center of the caldera, Redondo Peak. The floor bulged upwards when it rebounded, or "resurged", after removal of the weight of all the erupted magma, and because new, relatively degassed magma gradually inflated the top of the magma chamber. It was at this time that a series of viscous lava domes were erupted around the central buldge.

Bandelier Ashflow Tuff sitting on Permian red rocks (Abo and Yeso Formations)

Photo, L. Crumpler

Bandelier Ash Flow Tuff, Rendija Canyon near Los Alamos. Photo, L Crumpler

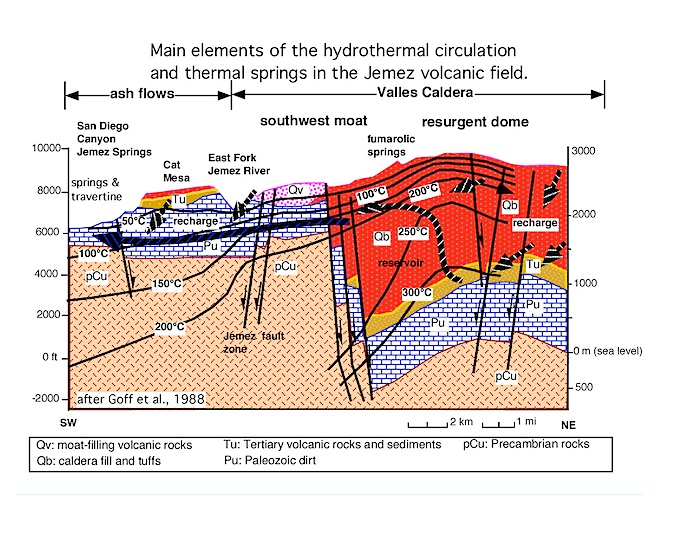

Hydrothermal Activity in the Valles Caldera

Although young and morphologically better developed than the Yellowstone caldera, hydrothermal activity in the Valles Caldera is limited. This is due, in part, to the relatively dryer environment relative to Yellowstone. It is also a function of the slighter greater age of the Valles system. Numerical models of heat transfer by fluid convection around large rhyolite magma chambers shows that the rate of heat loss is great. Unless continued magma injections occur to replace the heat loss, the thermal system will decline. The Valles caldera has been cooling for about 1.1 Ma since the caldera-forming eruption, and 0.5 Ma since the last rhyolite dome eruptions inside the caldera.

The following table summarizes the estimated thermal output of the three youngest, large ash-flow calderas in the continental Unites States.

| Caldera | Thermal Energy | Age |

|---|---|---|

| Yellowstone, WY | 5000 MW | 0.6 Ma |

| Long Valley, CA | 180 MW | 0.76 Ma |

| Valles, NM | 70 MW | 1.1 Ma |

Summary of Thermal Activity

- Hydrothermal activity initiated about 1 Ma

- Concentrated on SW resurgent dome and western ring-fracture areas

- Mostly dilute groundwater heat by high-temperatures at shallow depths

- Result of convective circulation of water over deep,hot central caldera rocks

- Meteoric water recharges the system; 300°C at depth of 2 to 3 km

- Convection in deep reservoir with “vapor cap”

- Liquid-dominated system at depth ascends convectively to 500 to 600 m depth

- Top of system is “vapor capped” by subsurface boiling at about 200°C

- Heats shallow levels that are diluted with groundwater flowing laterally

- Springs are acid-sulfate waters

- Result from condensation of steam and oxidation of H2S to form sulfuric acid

- Mixes with near-surface groundwater flowing from northern and eastern moat basins - Water flows laterally from top of system down hydrologic gradient

- Thermal waters flow down gradient outside of ring fracture in San Diego Canyon

- Vapor cap formed after breaching of SW caldera margin by ancestral Jemez River

- Resulted in draining of intracaldera lakes

- Lowered hydraulic head resulted in drop of maximum elevation of liquid in reservoir

Section through the southwest margin of the caldera. Hot water spills out of the caldera and flows down the hydrologic gradient. At certain locations, such as Soda Dam, the ground water iencounters a significant fault and follows the fault zone to the surface. Modified from Goff et al (1989).

The popular Tent Rocks recreational trails area represents debris shed off some of the earliest eruptions from the Jemez Mountains. This is an aerial oblique view looking north. For context, the caldera is out of the view to the left (west) and the city of Santa Fe is out of the view too, but on the right.

The tent rocks geomorphology is a result of rapid incision of the relatively soft volcanic tuff and volcanoclastic materials and perching of relatively resistant blocks of volcanic debris. Rapid incision occurs because, like most semi-arid locations, most of New Mexico's rain fall comes in brief burst during very limited times of the year. The run-off instead of run-in together with soft ash and silt encourages local gullying, which further encourages localized gully incision in the same location. Hence, deep incision and little back-wasting occurs without much weathering and rounding of the landforms.

View Valles Caldera in a larger map

General References

Goff, Gardner F.J.N., Baldridge, Hulen, J.B., Nielson, D.L., et al., 1989, Volcanic and hydrothermal evolution of the Valles caldera and Jemez volcanic field. N. Mex. Bur. Mines Miner. Resour. Mem, 46, 381-434.

Heiken, G., Goff, F, Gardner, J.N., Baldridge, W.S., Hulen, J.B., Nielson, D.L., and Vaniman, D., 1990, The Valles/Toledo caldera complex, Jemez volcanic field, New Mexico. Ann. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci., 18, 27-53.

Lipman, P. W., 1984, The roots of ash flow calderas in western North America: Windows into the tops of granitic batholiths. Jour. Geophys. Res., 89, 8801-8841.

Self, S., G. Heiken, M. L. Sykes, K., Wohlethz, R. V., Fisher, and D. P. Dethier, 1996, Field excursions to the Jemez Mountains, New Mexico. New Mex. Bur. Mines, Min. Resour. Bulletin 134.

All text and photo credit due to Dr. Larry Crumpler, New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science