You are here

Chapter 6: Fire in the Rio Grande Bosque

Fire in the bosque! Dry weather and a changes bosque ecosystem have made this a common cry in recent years. Large bosque fires have increased public awareness of this fragile ecosystem, but there is still much to learn about riparian fires. Even land managers are still trying to understand the role that fire plays here and the best ways to protect bosque plants and animals. Just what do we know?

Contents

Fire in the Bosque

By Lisa Ellis, Ph.D.

University of New Mexico Department of Biology

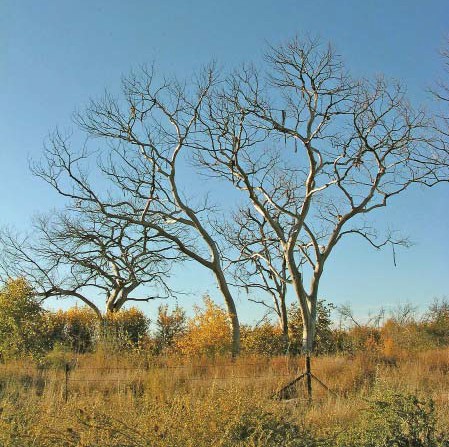

Fire in the bosque! Dry weather and a changed bosque ecosystem have made this a common cry in recent years. Large bosque fires have increased public awareness of this fragile ecosystem, but there is still much to learn about riparian fires. Even land managers are still trying to understand the role that fire plays here and the best ways to protect bosque plants and animals. Just what do we know?

Fires are quite common in the southwestern U.S., particularly during the normally dry late-spring-to-early-summer season. In addition, regional fire patterns are tied to the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycles: many large fires typically occur throughout the region during years influenced by the dry La Niña phase, when precipitation is well below average. Since the early to mid-1900s, the frequency of dry summers has increased, there have been more human-caused fire ignitions and fuels have accumulated due to fire suppression. Consequently, frequency, size and severity of fires in the region also appear to be on the increase.

Until recently, fire suppression was the goal of wildland resource management. Land managers now recognize the important role of fire in many of our natural ecosys- tems. In grasslands and ponderosa pine forests, for example, periodic disturbance from fire is important. Plants in these ecosystems have adaptations to survive fires, and they respond quickly after these events, by re-sprouting or releasing seeds. Many species fully depend on fire for regeneration. Fire also helps to break down nutrients from standing plant material and returns them to soil, making them more available for future plant uptake.

The role of fire in lowland riparian forests of the arid Southwest, however, is not well known. Although the Rio Grande bosque must have experienced fires, it seems likely that fire was not an important part of this system prehistorically. Native Americans may have burned the bosque occasionally to clear for agriculture, and grassland fires may have burned into the riparian zone from surrounding uplands, but fires would have been less severe than they are today due to lower fuel supplies. Before people altered the river and decreased the frequency and extent of flooding, flooding promoted decomposition of leaves and wood, and thus decreased accumulations of fuels available for fires. In addition, flooding dampened the forest floor and thus directly inhibited fires. Since humans have altered the natural flow regime along the Rio Grande, the decrease in flooding has resulted in an increase in fuel loads, and subsequently fires, in the bosque.

These lowland riparian bosques are adapted to disturbance, particularly to flooding and herbivory by animals such as beavers, but it is unlikely that fire was among the important forces shaping the evolution of Rio Grande cottonwoods. Re-sprouting is a common adaptation among some cottonwood species to disturbance by flooding and by other forms of severe defoliation (loss of leaves). Cottonwoods can re-sprout from their roots and from the base of the trunk after light fires, but in severe fires, mature tree mortality is very high. Typically, all above-ground tissues are killed in severe fires. Other plants native to Rio Grande riparian bosques also can re-sprout after less severe fires, including species such as seepwillow, New Mexico olive and Goodding’s willow. However, long-term data on post-fire survival for these species are unavailable, so our understanding of fire in this ecosystem remains limited.

Over the last century, non-native plants have flourished in the bosque, bringing different dimension to fires that occur there. Some non-native plants, particularly saltcedar, also sprout well after lighter fires. Further, the accumulation of the very flammable leaf litter from saltcedar is thought by some researchers to promote fires. Although the leaves contain volatile oils, they also tend to have a high moisture content, so it is the accumulation of leaf litter and dead woody material within the plants that increases flammability. One consequence of severe fires that kill the large cottonwoods is that after the mature trees fall, clearings are created that provide habitat for the establishment of new trees. Prior to the invasion by saltcedar and alteration of the river’s flow, these clearings would have been flooded and colonized by young cottonwoods and other native plants. Today, however, they are more often colonized by saltcedar, which releases seeds over a longer period of time and can take advantage of late-summer rains for establishment. Further, saltcedar has been observed to flower more heavily after a fire (stress-induced flowering), which increases the production of seeds available to colonize these clearings. Thus saltcedar may both promote and benefit from large fires in the bosque.

Fire needs three elements to burn: heat, fuel and oxygen. These three elements make up the fire triangle, and all three must be present for fire to ignite and spread. The initial heat is provided by an ignition source, for example a lightning strike, a lighted cigarette or a stray firework. This source of ignition must find sufficient fuel to burn, such as dry leaves and grasses, dead trees or fallen branches; there must be both something that lights easily to start the fire and a sufficient quantity of fuel to maintain it. Oxygen is readily available in the air. Weather conditions can affect the likelihood of a fire occurring. Hot temperatures and dry winds—conditions typical of late spring and early summer in New Mexico—promote the spread of fire, while fires are less likely to occur in cold and wet conditions.

How Do We Fight Bosque Fires?

The Rio Grande bosque is part of both urban and agricultural communities and is a wildland–urban interface where fire in one threatens the other. A house fire can start a bosque fire, and a bosque fire can start a house fire. Reducing fire risk in the bosque is an important part of protecting adjacent communities. The Wildland Fire Task Force of the City of Albuquerque is charged with suppressing any wildland fires that occur within the Albuquerque city limits and surrounding areas. The task force includes personnel and equipment from six fire stations that are located either by the Rio Grande bosque or on the east or west mesas. These personnel are specifically trained to fight wildland fires. Fire-fighting equipment used by this crew includes front-line emergency response equipment as well as two brush trucks (one capable of foam production) and two four-wheel-drive all-terrain vehicles (with a towing trailer). These crews are also equipped with personal protective equipment, portable drafting pumps and hand tools designed for wildland or brush fire fighting. Similar equipment is used by crews along other reaches of the Middle Rio Grande Valley.

Fires in the bosque provide some unique obstacles in suppression. The primary constraint is due to restricted access within the levees. Jetty jacks represent very real obstacles to fire fighting access—trucks cannot get into much of the bosque area due to jack lines. Only smaller trucks are able to follow levee roads. Hand crews face problems, too—Russian olive and black locust have very painful thorns!

Fire suppression techniques depend in part on the size of the fire. With flames up to three feet (1 m) high, firefighters can fight the fire directly with hand equipment. Bulldozers are used to fight flames that exceed three feet, up to 12 feet (1–4 m). Water drops from helicopters and cargo planes are used when flames exceed 12 feet (4 m).

Recent Fires in the Bosque

Today, fires in the bosque tend to be caused by humans, with lightning-caused fires being relatively rare. During a 10-year study period (1986–1995), UNM graduate student Mary Stuever found that most fires in the Middle Rio Grande bosque occurred between February and April, though in some years there was an increase in mid-summer and/or fall fires. One of the main causes of bosque fires—debris burning—typically occurs during the late-winter to early-spring period when farmers are preparing fields and acequias for the growing season. Other common causes of bosque fires include arson, illegal campfires, children and careless disposal of smoking materials.

New Mexico State Forestry Division data show that 534 fires occurred on Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District lands in the Middle Rio Grande Valley during 1993–2003, with fires burning in all months of the year. By far most fires occurred during February through July. Very large fires were not common; only 4 percent of all fires burned over 100 acres (40 ha (hectares, a metric unit of area equal to 10,000 square meters or 2.471 acres)), with most fires (82 percent) less than 10 acres (4 ha) in size, and 14 percent of all fires burning between 10 and 99 acres (4 and 39.6 ha). All fires that burned over 100 acres (40 ha) occurred during March through June, with 13 of these 23 fires occurring in April. Most of these large fires burned in Socorro County.

Post-fire recovery work in the Valley has changed over the years as our understanding of the system and management options has grown. Initially, burned sites were simply left alone, with no post-fire restoration attempted. Later, restoration work focused on replanting native trees into large monocultures, with no effort to plant understory shrubs or grasses. Burned stumps were ground out and removed. Now there is more of an attempt to restore the mosaic of habitats once present in the valley. In addition to pole-planting cottonwoods and willows, workers plant understory shrubs and spread seeds for native grasses. Stumps of native species are left to re-sprout and constructed wetlands may be added. Heavy machinery is often used to remove burned wood from sites or to chip remaining wood. Herbicides are sometimes used to kill stump-sprouts of exotic species such as saltcedar, with follow-up treatments in subsequent years. Remaining live native trees are protected and some dead snags are left for habitat enhancement, providing homes for wildlife. Some sites are now monitored after restoration efforts are completed to measure progress and gauge the success of the project.

Changes in bosque management are needed to decrease the impact of fires. Researchers and land managers have finally come to a seemingly radical approach to the preservation and restoration of Rio Grande bosque after more than a decade of work focused on understanding this dynamic ecosystem. Published in 2005, the Bosque Landscape Alteration Strategy (BLAS) was developed by numerous scientists, land managers and others interested in preserving the bosque. The strategy focuses on re-creating a patchy mosaic of native riparian trees and open spaces along the narrow active floodplain, within the current levee system, between Cochiti Dam and the upper end of Elephant Butte Reservoir. The goals of this rehabilitation/remediation/restoration strategy are to decrease the potential for bosque wildfires and to decrease water loss due to evapotranspiration, while trying to replicate the mosaic of habitats once present along the Middle Rio Grande Valley. The strategy will reduce the now often-continuous forest into patches of trees interspersed with meadows and wetlands. Active implementation of the BLAS should result in a very different floodplain than the one we know today, but this will be a landscape more like that present prior to human intervention and one much less prone to devastating wildfires.

The BLAS provides new guidelines for bosque management, which are being incorporated by numerous agencies actively working to reduce the potential for and the impact of fires in the bosque. One multi-agency restoration plan already underway, the Bosque Wildfire Project, involves the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the City of Albuquerque Open Space Division, the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District, the Corrales Bosque Preserve, Village of Corrales, the Pueblo of Sandia, the Pueblo of Isleta, the New Mexico State Forestry Division and others. The project seeks to selectively thin areas with high fuel loads and/or non-native vegetation, to remove jetty jacks and debris, to improve emergency access (drain crossings, levee road improvements and construction of turn-arounds) and to revegetate burned and thinned areas. The project area includes the Albuquerque Reach of the Rio Grande bosque (also known as the Rio Grande Valley State Park), the Corrales Bosque Preserve and locations within the Pueblos of Sandia and Isleta. Similar work is being done by the Socorro Save Our Bosque Task Force for Socorro County, as well as at other sites along the valley.

One of the main strategies used now to prevent fires is the removal of non-native vegetation and dead and down woody debris from areas that have not burned. This involves large-scale removal of dead trees and fallen branches using heavy equipment such as brush cutters and Bobcats; the wood is typically either removed from the site and offered to the public as firewood or chipped and spread across the site in an attempt to restore nutrients to the forest. This fuel load reduction, however, has brought mixed reactions. While it appears that decreasing accumulations of woody debris on the forest floor and removing non-native shrubby plants will decrease the potential for devastating fires and help to protect native cottonwoods, this also removes habitat for certain native animals. In particular, there has been controversy over removing habitat for shrub- and ground-nesting birds. Studies have shown that overall bird species richness is enhanced by the presence of a variety of habitats within the bosque corridor—such as the presence of sand bars and meadows, thick brushy understory, mid-level shrubs, as well as mature trees. There has been concern that removing understory vegetation and woody debris will remove much of these available habitats. Some clearing is being done in stages over several years to allow native plants to get established in partially cleared areas before all non-native plants are removed. Certainly it is important that clearing is done during the non-breeding season to protect nesting birds. Clearing done during the breeding season causes nest abandonment and can directly kill birds. Revegetating with native shrubs will be important to maintain the shrub habitat needed by certain avian species.

One message concerning the bosque is clear from the recent increase in wildfires: a healthy bosque will not survive without active intervention and management and indeed without drastically new management practices. Perhaps ironically, what is needed are changes that approximate the structure and functioning of the old system—albeit within the spatial constraints of the present system—and a reduction of regulatory activities that impact the river’s natural flow regime. We now know that we must take our lessons from the river itself and restore or rehabilitate what we have changed, in order to save this unique ecosystem.

Selected Bosque Fires

To best understand the effect of fire in the bosque, it is helpful to visit a burned site. The following is a summary of some recent and better known fires in the Middle Rio Grande Valley (information from the City of Albuquerque Open Space Division, the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District and the Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge). Look at the Bosque Education Guide web site for additional sites.

Montaño Fire

When: June 25, 2003

Where: Montaño Bridge at all quadrants. Source of fire was from the northwest section.

Size: 113 acres (46 ha)*. The northwest quadrant burned 67 acres (27 ha). Started on public land and spread to private land.

Cause: Human-caused (cigarette)

Recovery work: Large burned trees were cut down and cut into firewood-size pieces. Most of the wood was made available to the public as free firewood. There was less chipping in this area compared to the I-40 fire (see below). Larger open areas were seeded with native grasses and cottonwoods were pole-planted. Exotic stump re-sprouts were sprayed with herbicide. Native stump re-sprouts were caged to protect against beavers. Open Space Division and students are monitoring on- going recovery.

I-40 (Atrisco) Fire

When: June 24, 2003

Where: On both sides of the river, mostly north of the I-40 bridge, to just south of Campbell Road (south of the Nature Center Discovery Pond)

Size: 150 acres (61 ha). Started on public land, spread to private land

Cause: Human-caused (fireworks)

Recovery work: Large burned trees were cut down and most of the wood was chipped and spread on the ground. Some larger pieces were offered to the public as firewood. Some cottonwood and willow poles were planted. Larger areas farther from the water table were seeded with native bosque grasses. Exotic re-sprouts from stumps were sprayed with herbicide while native re-sprouts were protected with beaver caging. Open Space Division and students are monitoring recovery.

La Orilla Burn

When: April 23, 2002

Where: West side of river between La Orilla and Paseo del Norte

Size: 35 acres (14 ha)

Cause: Human-caused (illegal campfire)

Recovery work: Burn recovery included 1,100 new trees and shrubs planted in the burn area. Replanting was a coordinated effort between the City Open Space Division, Tree New Mexico, schools and other volunteer groups.

San Pedro Fire

When: June 8, 1996

Where: Near the community of San Pedro, north of Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge. The fire burned south and into the refuge.

Size: Approximately 6,000 acres (2,428 ha) total, with 1,640 acres (656 ha) within the Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge

Cause: Human-caused (arson)

Recovery work: (This summary is based primarily on work done within the Refuge.) Recovery work includes extensive exotic control, using an excavator to remove root crowns with little soil damage, clearing with root plows and root rakes and treating sprouts with herbicides. Cross dikes and water delivery systems were added in some places to manage water levels and promote native tree germination. Refuge personnel, along with members of the Socorro Save Our Bosque Task Force, developed a conceptual plan for restoration of the whole valley (Socorro area), including San Pedro burn areas. Other procedures include monitoring physical and biological aspects of the system and removing some of the man-made infrastructure.

* ha = hectares, a metric unit of area equal to 10,000 square meters or 2.471 acres

A Glossary of Fire Terms

Canopy is the uppermost branches of trees forming a continuous cover of leaves at the top of a forest.

Crown fire is a high-severity fire that reaches up into the forest canopy.

Fire adaptation is a characteristic that enhances the ability of an organism to survive fires.

Fire break or fuel break is a natural or man-made barrier that lacks fuel sufficient to maintain a fire.

Fire dependence refers to natural communities that are adapted to fire and that rely on fire for maintaining conditions needed by plants and animals in those communities. Such a system may be called a fire-dependent ecosystem.

Fire ecology is a branch of ecology that studies the origins of wildland fire and its relationship to the ecosystem.

Fire history indicates how often fires occur in a given geographical location.

Fire-independent ecosystem is a system that does not have fires at all, either because there is no ignition source or due to a lack of vegetation.

Fire intensity is a measure of heat generated by a fire. This can only be measured during the fire, so typically fire severity (see below) is a more useful measure when making observations at a site after it has burned.

Fire regime reflects the characteristics of fire in a given ecosystem over time, such as the frequency, predictability, intensity and seasonality of fire. This is basically the role that fire plays in that ecosystem.

Fire scar is a mark on a tree produced by a layer of charcoal (a burned layer) that is then enveloped by a layer of new growth.

Fire-sensitive ecosystem is a system that evolved without the influence of repeated fires, in which the plants and animals generally lack adaptations to come back after fires.

Fire severity is a measure of the degree to which a fire alters a given site. Fire severity can be determined after a fire, based on characteristics such as the extent of burn (char) on a tree or the amount of leaf litter remaining on the ground, and this is used to estimate the effects of fire intensity.

Fire triangle indicates the three elements needed to start and maintain a fire: heat, fuel and oxygen.

Fuel ladder is dry or volatile plants of different heights that carry fire up to the tops of trees, such as fallen trees, branches or exotic plants (saltcedar, Russian olive).

Ground fire is a fire burning on the ground or through the understory and not reach- ing into the canopy.

Prescribed burn/prescribed fire is a fire intentionally set under known conditions of fuel, weather and topography to achieve a specific management goal.

Reclamation is the act or process of bringing wild or waste land into a condition for productive use, or repairing an area after activities such as mining or fire (typically modifying an area to be of some use to humans).

Restoration is the process of restoring an area to its natural condition (or a condition that mimics the natural condition as nearly as possible).

Topography is the surface features of a place, the contours of a landscape large or small.

Wildfire is a non-structural fire (not in a building), other than a prescribed fire, that occurs in a forest or other wildland area.

Wildland–urban interface is land close to or within forested area that contains houses and other buildings.

References

Bosque Landscape Alteration Strategy Objectives, Basic Requirements and Guidelines. 2005. Yasmeen Najmi, Sterling Grogan and Cliff Crawford. Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District, Albuquerque, NM.

Resources

The Corps of Engineers has a web site with maps of burned areas.

The New Mexico State Forestry Division maintains a list of bosque fires at emnrd.state.nm.us.

Chapter 6 Downloads and Activites

Chapter 6: Fire in the Rio Grande Bosque (2.08mb PDF)

Activities

- Fire Vocabulary (174 kB PDF)

- A Spectrum of Fires (164 kB PDF)

- Post-Fire Survival of Bosque Trees (520 kB PDF)

- Naturalist Notebooks: Fire (213 kB PDF)

- Changing Fire (490 kB PDF)